O Glory of the All-Glorious!

My personal prototype, or ideal type, for devotion is the Bhakti or Bhakti-Ṣūfī movement of South Asia, including the Indus Valley. I briefly discuss that historical movement’s spiritual impact in two Internet radio broadcasts (MP3 audio file 1 and MP3 audio file 2). The movement’ influence upon South Asia, and even in the Western world, has endured to the present time. Moreover, this stirring copresence of the heart (al-qalb) was formalized in the Sikhism of Gurū Nānak (1469-1539) and in other lumpenproletarian (from German and Latin, ragged “baby-factories”), or underclass, communities from South Asia.

al-ʾAndalus (الأندلس), a word with a disputed etymology, was a medieval Muslim state (roughly, 711-1492 A.D.) which included modern Portugal, Andorra, Spain, and a portion of South France. The Muslim inhabitants of that region have been popularly called the “Moors.” Moreover, according to Shoghi Effendi, the Golden Age of Islām began, partially, in the “outlying territories” of Europe:

In my humble opinion, the devotional center, or flowering, of that Golden Age can be found in the heart-centered Bhakti-Ṣūfī movement. Heartfulness Inquiry™, The Unicentric Paradigm™, and Unities of All Things™ in general are devotionally anchored in that South Asian confluence of two spiritual streams. Adopting a critical and postcolonial academic perspective to the movement, both Bhakti and Ṣūfī reverential associations in India arose largely from within subaltern (subordinate, oppressed, dominated, or hegemonized) peasant populations, including women, lower-caste Hindūs, and Muslims:

Some insight into the spiritual stature of Gurū Nānak was provided in a letter by the National Spiritual Assembly (NSA) of the Baháʾís of India, dated July 7, 1986, to the State Baháʾí Council of Punjab. That NSA received a letter from the Universal House of Justice, dated October 27, 1985. According to the House of Justice, Gurū Nānak was endowed with a “saintly character.” Moreover, he “was inspired to reconcile the religions of Hinduism and Islam, the followers of which religions had been in violent conflict.” Therefore, the House of Justice blessed Gurū Nānak as a “saint of the highest order”, or, perhaps, a walī Allāh (friend of God).

Additionally, in Hindūism, the Acintyabhedaābheda (Sanskrit for inconceivable oneness and difference) bhakti tradition originated in Gauḍīyā Vaiṣṇava (Sanskrit for Viṣṇu or Vishnu worship in the Gauḍa territory of modern-day Bangladesh and Bengal, India). It was founded by Caitanya Mahāprabhu (1486–1534 A.D.) and more recently popularized, in the West, by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (Abhaya Caraṇāravinda Bhaktīvedānta Svāmī Prabhupāda, 1896-1977 A.D.). Caitanya’s teaching, in the Bhakti-Ṣūfī movement, was uncomplicated. Many later leaders complicated it.

The following is a complete translation of the only known text authored by Caitanya Mahāprabhu, Śrī Śikṣāṣṭakam (Sanskrit for an instruction in eight stanzas):

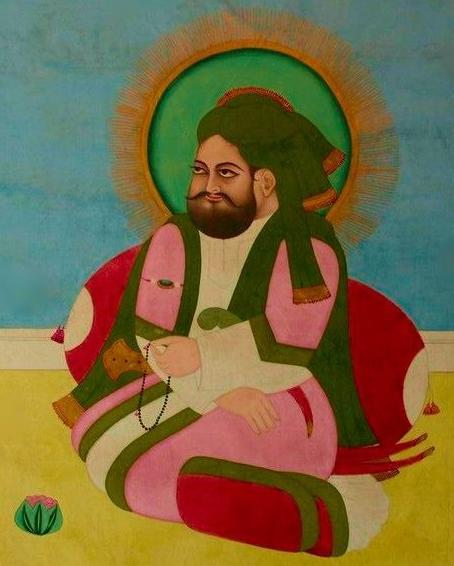

Ḥaḍrat Sulṭān Bāhū, as a Ṣūfī from the South Asian subcontinent, was another beautiful exemplar of that traditionally commingled, or interfaith, devotional experience. Like Gurū Nānak and Caitanya Mahāprabhu, Bāhū became a brilliant luminary of the Bhakti-Ṣūfī movement (approximately 800-1700 A.D.):

I have been a Baháʾí since 1970. I am not a Muslim. Nevertheless, I have been inspired by the deep Ṣūfism (Arabic, Taṣawwuf) of the heart in the poetry and prose of Sulṭān Bāhū. While a mystic by temperament, Bāhū also emphasized the importance of faithfulness to al-Šarʿī’a (Arabic for the Prescription or legal code) within the beautiful religion of Islām. In my view, al-walī Allāh (the friend of God or saint), Sulṭān Bāhū, is among the finest fruits of the religion of Islām. He has been accurately designated, al-Sulṭān al-ʿArifīn (the king or chief of mystic knowers or gnōstics). I have lovingly and sincerely cherished his blessed soul during my inner communions with him.

Acting from the world beyond, beloved Bāhū, peace and blessings be upon him, believe he was among the spiritual sources of the visionary flashing white lights, lightning bolts, or chalices of pure light. Through Bāhū, the discovery of Ṣūfī meditation, and Ṣūfism (Taṣawwuf) more broadly, became, to my understanding, the Blessed Beauty’s chosen instrument of healing from my heart-based deficits as an Autist. Indeed, although I only recognized the eminent Bāhū’s influence upon me in 2011, he may have been with me, guiding me, for my entire life.

The Blessed Perfection led me to Himself, I believe, through a Ṣūfī-type meditation. When I began practicing it in 2010, dear Bāhū, a Muslim during the Islāmic Dispensation, entered my heart and, I strongly feel, showed me the way to my Lord, Bahāʾ. For some inexplicable reason of the heart, I was drawn, above all else, to beloved Bāhū while studying Ṣūfism. My first sensations of empathy, as an Autist, revolved around, first, the pure soul of Bāhū and, second, my adoration for the Blessed Seal Muḥammad as the Source of Ṣūfism. He has been the Object of such misunderstanding. By turning to this man of the heart, I got my own. As Bāhū wrote in one of his inspiring treatises:

Once Bāhū rejected disunity or dualism for unity or nonduality, he was emancipated:

Since I was a child, I have been passionate about both Islāmicate, or Islāmically contextualized, thought and Indian traditions, including Hindūism or Sanātana Dharma (Sanskrit for eternal support), Sikhism, and Sūrat Śābda Yoga. Following a meditation on August 17, 2013, I realized that my lifelong inner connection with dear Bāhū might have kindled these twofold interests. Current illustrations include Ṣūfī Information Central™ and Heartfulness Inquiry™, my love for British phliosopher Roy Bhaskar’s philosophy of metaReality. This latest version of his Critical Realism was significantly influenced by a journey toward rediscovering his own Hindū heritage, including bhakti yoga.

Specifically, I have been attracted to the Bhakti-Ṣūfī movement throughout my life. Before I became a Baháʾí, I seriously considered becoming a Sikh. I was deeply disappointed after discovering, through mail correspondence with the Sikh Temple in Stockton, CA, that baptized Sikhs needed to carry a sword and to wear both a turban and long underwear draped around the knees. Since I was already being bullied as an Autist, such unusual accoutrements, especially in the gym locker room, would have only made matters worse. I was not told that not all Sikhs follow those conventions. Perhaps dear Bāhū was protecting me for Baháʾuʾlláh.

Although I was unsuccessful at astral projection or out-of-body experiences, I did come close to joining the neo-Sikh Eckankar organization. It incorporates a similar practice to astral projection. This Americanized branch of the highly schismatic Sūrat Śābda Yoga (Arabized Sanskrit for union through attention to the word) was founded by John “Paul” Twitchell (1909-1971) in 1965. As I recall, only a minor postal miscommunication between me, at around thirteen-years old, and the headquarters (then in Las Vegas, NV), possibly through Bāhū’s intercession, prevented me from becoming a member. Their return letter may have dampened my enthusiasm, but I had already lost interest.

Yet, in my continuing search for angelic contact, I was initiated, after becoming a Baháʾí, into three other Sūrat Śābda Yoga “divisions” or groups: Sri Sri Thakur Anukulchandra Satsang (Śrī Śrī Ṭhakura Anukulācandra Satsaṅga, named for the founder of the organization, 1888-1969), Sant Mat (Sanskrit, Saṅt Mata, the realized one’s doctrine or path), and Spiritual Freedom Satsang (an offshoot of Twitchell’s Eckankar). Any movement, like Sūrat Śābda Yoga, which promotes a primary reliance upon subjective knowledge, or gnōsis, of alleged beings, locations, lights, and sounds in supposedly higher dimensions of existence can rapidly factionalize.

As a matter of record, his angelic presence Sulṭān Bāhū, a Punjābī, was born in Angāh (in the present-day Pākistānī Punjāb), around 1628 A.D., and he died about 1691. His mausoleum is located in Gaṛh Mahārāja (Hindūstānī or “Hindī-Urdū” for Fort of the Great King, which is now in Pākistān). Etymologically, bā is the Fārsī/Persian preposition for “with,” while hū is the Arabic pronoun for “he” (referring here to God). Therefore, Bāhū, which was Sulṭān Bāhū’s given name (from his mother, Bībī Rāstī, Persian for madam truth), can be translated as “with God.” His name came to define his noble character. As Bāhū wrote, in one of his poems, referring to the modest spelling differences between two letters:

Bāhū is regarded as al-imām (Arabic for the pathfinder or founder) of the Sārvarī Qādirīyah Ṣūfī Ṭarīqat (Persianized Arabic for order). Although he would not designate an heir, much as Rebbe Naḥman (1772-1810) of Bratslav Ḥasidic Judaism refused to establish a dynasty (Hebrew, hā-ṣadiqîm, the righteous ones), each has had one or more claimants to succession. Qādirīyah is named after the traditional founder of the original order, ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Gīlānī. Al-Qādir (the capable or competent one) is one of the ninety-nine names of Allāh. Sārvarī (Persian, Hindī, and Urdū for chiefship) refers here to the ʿUwaysī transmission, under the sovereignty of the Blessed Muḥammad, to Bāhū.

Briefly, the word, “ʿUwaysī,” was adopted from the reported case of His Blessed Presence Muḥammad’s contemporary, ʿUways al-Qaranī. According to traditional accounts, he swore or, literally, “sold” (bayʿah), with a metaphorical handshake (more precisely, a handclasp), his allegiance to the Prophet of Islām wholly in the world of spirits (al-ʿālam al-arwāḥ). The two men never met physically. Although the circumstances surrounding the life of ʿUways al-Qaranī may be legendary, or partially so, he has inspired individuals to claim inner spiritual direction, and sometimes even authority over Ṣūfī orders, as a result of similar experiences.

In an ʿUwaysī transmission, authorization (al-iǧāza) is allegedly conveyed, entirely within the heavenly realms, by an outwardly unrelated entity (living, deceased, or even mythological). They have included the dear Prophet Muḥammad, the legendary al-Hiḍr (the Green One), and departed Ṣūfī shaykhs (al-šuyuh, elders), such as the founders of orders (al-ayimma or “imāms,” pathfinders). Soul to soul, sometimes within the otherworldly states of inspired dreams (al-manāmāt) and visions (al-ruʾan), vows of Ṣūfī loyalty, like the oaths of fealty owed to a European feudal lord in the Middle Ages, will be pledged one to another.

Ḥaḍrat Sulṭān Bāhū, God bless his soul, formulated taṣavvur-i ism-i ḏāt (Persianized Arabic for conceptualizing the personal name of God) or, in Arabic, al-taṣawwur al-ism al-ḏāt. The discipline involves visualizing the word, ﷲ (Allāh), being inscribed upon one’s own heart (Arabic, al-qalb). When, through the intercession of the exalted Bāhū, I was inspired, resurrected, and lovingly emancipated as an Autist, I incorporated my own revised version of the exercise into the methodology of Heartfulness Inquiry™. That spiritual application remains the devotional center of Unities of All Things™.

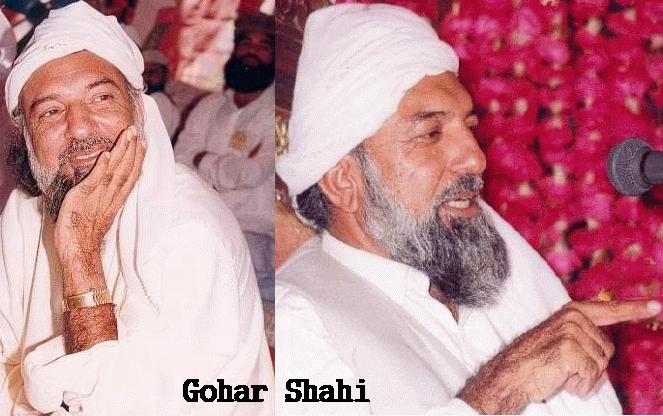

Intriguingly, before I was even consciously aware of beloved Bāhū, I sought out and received personal instruction from an authorized disciple of Gohar Shahi (Persian and Urdū, Guhar Šāhī, Jewel Imperial). He represented the U.S.-based organization, the American Ṣūfī Institute (Devil’s Lake, ND). It has since been renamed as al-Markāz-i Rūḥānī Qādrī, the Spiritual Center of Qādrī (al-Qādirīyah Ṣūfism). This group, presently located in the Jamshoro District (Urdū, Ḏilā-i Ǧāmšūrū) of Sindh, Pākistān, regards Gohar Shahi as a Sunnī Muslim, not as a mahdī or messiah, who welcomed people from all religions.

Gohar Shahi taught various meditative practices, including a type of taṣavvur-i ism-i ḏāt. As I discovered much later, Shahi, after claiming to have an inward, mystical experience with Bāhū, founded a similarly ʿUwaysī branch of Sārvarī Qādirīyah Ṣūfī Ṭarīqa, al-Qādirīyah al-Muntahī (the Qādirīyah order of the Adept), and he developed a set of teachings and meditative practice called the Religion of God (in Urdūized, as well as Persianized, Arabic, Dīn-i Ilāhī). He was, I feel, my personal gate to Ḥaḍrat Sulṭān Bāhū. Born in 1941, and now arguably deceased (2001 or 2003), Shahi is, I believe, my fellow traveller under Bāhū’s watchful eye:

On September 8, 2013, during a reflection, I realized that Bāhū reached out, though Gohar Shahi, and connected more deeply with me. Shahi was, at the time, still in this world:

Furthermore, as a child, I referred to a ventriloquial team, with myself and my younger sibling, as The Karachis. At the time, I was unaware of the origin of the term, but I must have heard it mentioned somewhere. In retrospect, I do not know why I did not call us, simply, The Fosters. Karāčī or Karachi (Urdū, کراچی), a bustling metropolis, is the most populous city in Pākistān and the third largest in the world. Then, on October 6, 2013, it occurred to me, during another reflection, that Ḥaḍrat Sulṭān Bāhū, who lived in modern-day Pākistān, was drawing me close to him.

Modern India has changed. Beloved Shoghi Effendi quoted from His divine Presence Baháʾuʾlláh and described secularism as a menace:

MarkFoster.NETwork Publications™